Android’s defense-in-depth strategy applies not only to the Android OS running on the Application Processor (AP) but also the firmware that runs on devices. We particularly prioritize hardening the cellular baseband given its unique combination of running in an elevated privilege and parsing untrusted inputs that are remotely delivered into the device.

This post covers how to use two high-value sanitizers which can prevent specific classes of vulnerabilities found within the baseband. They are architecture agnostic, suitable for bare-metal deployment, and should be enabled in existing C/C++ code bases to mitigate unknown vulnerabilities. Beyond security, addressing the issues uncovered by these sanitizers improves code health and overall stability, reducing resources spent addressing bugs in the future.

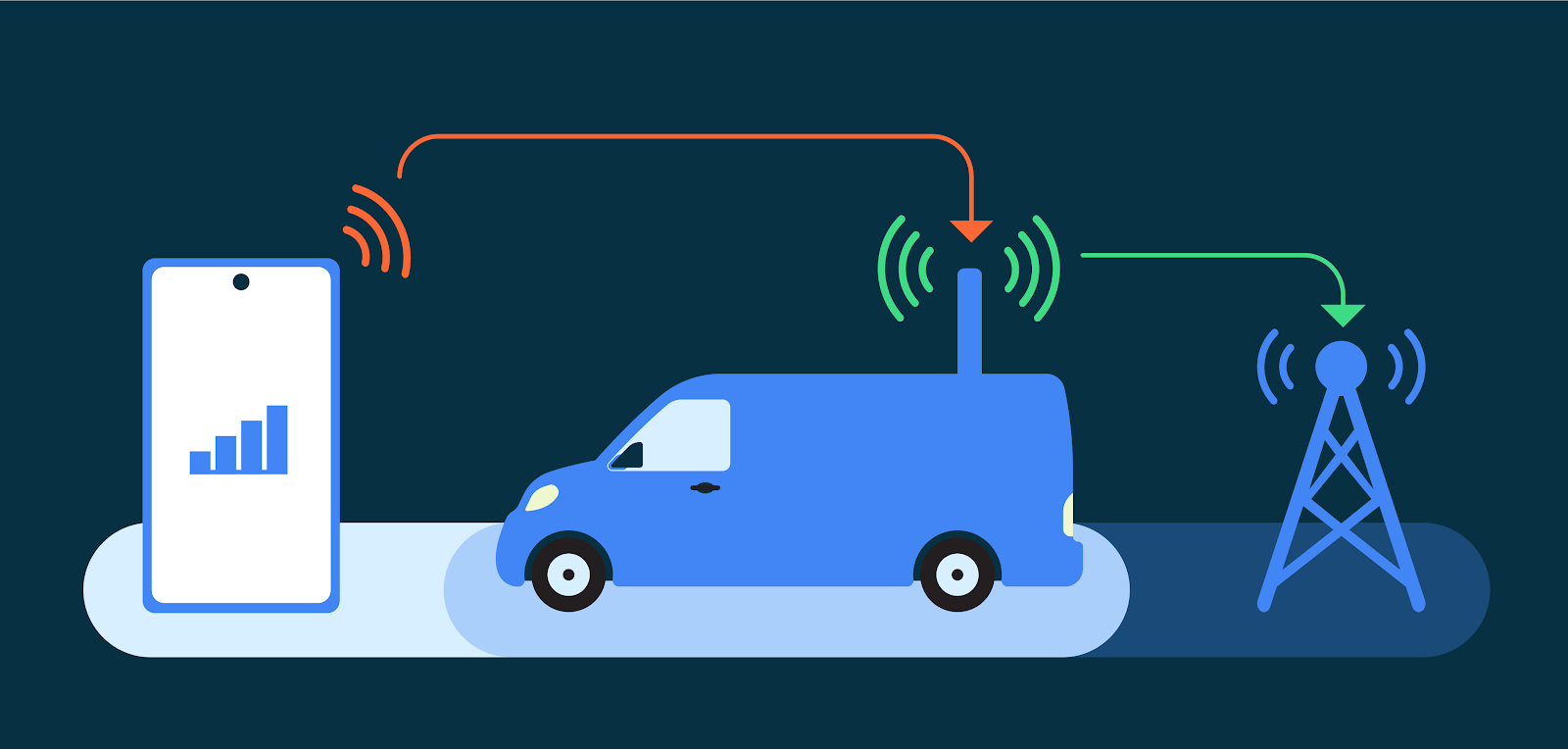

An increasingly popular attack surface

As we outlined previously, security research focused on the baseband has highlighted a consistent lack of exploit mitigations in firmware. Baseband Remote Code Execution (RCE) exploits have their own categorization in well-known third-party marketplaces with a relatively low payout. This suggests baseband bugs may potentially be abundant and/or not too complex to find and exploit, and their prominent inclusion in the marketplace demonstrates that they are useful.

Baseband security and exploitation has been a recurring theme in security conferences for the last decade. Researchers have also made a dent in this area in well-known exploitation contests. Most recently, this area has become prominent enough that it is common to find practical baseband exploitation trainings in top security conferences.

Acknowledging this trend, combined with the severity and apparent abundance of these vulnerabilities, last year we introduced updates to the severity guidelines of Android’s Vulnerability Rewards Program (VRP). For example, we consider vulnerabilities allowing Remote Code Execution (RCE) in the cellular baseband to be of CRITICAL severity.

Mitigating Vulnerability Root Causes with Sanitizers

Common classes of vulnerabilities can be mitigated through the use of sanitizers provided by Clang-based toolchains. These sanitizers insert runtime checks against common classes of vulnerabilities. GCC-based toolchains may also provide some level of support for these flags as well, but will not be considered further in this post. We encourage you to check your toolchain’s documentation.

Two sanitizers included in Undefined Behavior Sanitizer (UBSan) will be our focus – Integer Overflow Sanitizer (IntSan) and BoundsSanitizer (BoundSan). These have been widely deployed in Android userspace for years following a data-driven approach. These two are well suited for bare-metal environments such as the baseband since they do not require support from the OS or specific architecture features, and so are generally supported for all Clang targets.

Integer Overflow Sanitizer (IntSan)

IntSan causes signed and unsigned integer overflows to abort execution unless the overflow is made explicit. While unsigned integer overflows are technically defined behavior, it can often lead to unintentional behavior and vulnerabilities – especially when they’re used to index into arrays.

As both intentional and unintentional overflows are likely present in most code bases, IntSan may require refactoring and annotating the code base to prevent intentional or benign overflows from trapping (which we consider a false positive for our purposes). Overflows which need to be addressed can be uncovered via testing (see the Deploying Sanitizers section)

BoundsSanitizer (BoundSan)

BoundSan inserts instrumentation to perform bounds checks around some array accesses. These checks are only added if the compiler cannot prove at compile time that the access will be safe and if the size of the array will be known at runtime, so that it can be checked against. Note that this will not cover all array accesses as the size of the array may not be known at runtime, such as function arguments which are arrays.

As long as the code is correctly written C/C++, BoundSan should produce no false positives. Any violations discovered when first enabling BoundSan is at least a bug, if not a vulnerability. Resolving even those which aren’t exploitable can greatly improve stability and code quality.

Modernize your toolchains

Adopting modern mitigations also means adopting (and maintaining) modern toolchains. The benefits of this go beyond utilizing sanitizers however. Maintaining an old toolchain is not free and entails hidden opportunity costs. Toolchains contain bugs which are addressed in subsequent releases. Newer toolchains bring new performance optimizations, valuable in the highly constrained bare-metal environment that basebands operate in. Security issues can even exist in the generated code of out-of-date compilers.

Maintaining a modern up-to-date toolchain for the baseband entails some costs in terms of maintenance, especially at first if the toolchain is particularly old, but over time the benefits, as outlined above, outweigh the costs.

Where to apply sanitizers

Both BoundSan and IntSan have a measurable performance overhead. Although we were able to significantly reduce this overhead in the past (for example to less than 1% in media codecs), even very small increases in CPU load can have a substantial impact in some environments.

Enabling sanitizers over the entire codebase provides the most benefit, but enabling them in security-critical attack surfaces can serve as a first step in an incremental deployment. For example:

- Functions parsing messages delivered over the air in 2G, 3G, 4G, and 5G (especially functions handling pre-authentication messages that can be injected with a false/malicious base station)

- Libraries encoding/decoding complex formats (e.g. ASN.1, XML, DNS, etc…)

- IMS, TCP and IP stacks

- Messaging functions (SMS, MMS)

In the particular case of 2G, the best strategy is to disable the stack altogether by supporting Android’s “2G toggle”. However, 2G is still a necessary mobile access technology in certain parts of the world and some users might need to have this legacy protocol enabled.

Deploying Sanitizers

Having a clear plan for deployment of sanitizers saves a lot of time and effort. We think of the deployment process as having three stages:

- Detecting (and fixing) violations

- Measuring and reducing overhead

- Soaking in pre-production

We also introduce two modes in which sanitizers should be run: diagnostics mode and trapping mode. These will be discussed in the following sections, but briefly: diagnostics mode recovers from violations and provides valuable debug information, while trapping mode actively mitigates vulnerabilities by trapping execution on violations.

Detecting (and Fixing) Violations

To successfully ship these sanitizers, any benign integer overflows must be made explicit and accidental out-of-bounds accesses must be addressed. These will have to be uncovered through testing. The higher the code coverage your tests provide, the more issues you can uncover at this stage and the easier deployment will be later on.

To diagnose violations uncovered in testing, sanitizers can emit calls to runtime handlers with debug information such as the file, line number, and values leading to the violation. Sanitizers can optionally continue execution after a violation has occurred, allowing multiple violations to be discovered in a single test run. We refer to using the sanitizers in this way as running them in “diagnostics mode”. Diagnostics mode is not intended for production as it provides no security benefits and adds high overhead.

Diagnostics mode for the sanitizers can be set using the following flags:

-fsanitize=signed-integer-overflow,unsigned-integer-overflow,bounds -fsanitize-recover=all

Since Clang does not provide a UBSan runtime for bare-metal targets, a runtime will need to be defined and provided at link time:

// integer overflow handlers __ubsan_handle_add_overflow(OverflowData *data, ValueHandle lhs, ValueHandle rhs) __ubsan_handle_sub_overflow(OverflowData *data, ValueHandle lhs, ValueHandle rhs) __ubsan_handle_mul_overflow(OverflowData *data, ValueHandle lhs, ValueHandle rhs) __ubsan_handle_divrem_overflow(OverflowData *data, ValueHandle lhs, ValueHandle rhs) __ubsan_handle_negate_overflow(OverflowData *data, ValueHandle old_val) // boundsan handler __ubsan_handle_out_of_bounds_overflow(OverflowData *data, ValueHandle old_val)

As an example, see the default Clang implementation; the Linux Kernels implementation may also be illustrative.

With the runtime defined, enable the sanitizer over the entire baseband codebase and run all available tests to uncover and address any violations. Vulnerabilities should be patched, and overflows should either be refactored or made explicit through the use of checked arithmetic builtins which do not trigger sanitizer violations. Certain functions which are expected to have intentional overflows (such as cryptographic functions) can be preemptively excluded from sanitization (see next section).

Aside from uncovering security vulnerabilities, this stage is highly effective at uncovering code quality and stability bugs that could result in instability on user devices.

Once violations have been addressed and tests are no longer uncovering new violations, the next stage can begin.

Measuring and Reducing Overhead

Once shallow violations have been addressed, benchmarks can be run and the overhead from the sanitizers (performance, code size, memory footprint) can be measured.

Measuring overhead must be done using production flags – namely “trapping mode”, where violations cause execution to abort. The diagnostics runtime used in the first stage carries significant overhead and is not indicative of the actual performance sanitizer overhead.

Trapping mode can be enabled using the following flags:

-fsanitize=signed-integer-overflow,unsigned-integer-overflow,bounds -fsanitize-trap=all

Most of the overhead is likely due to a small handful of “hot functions”, for example those with tight long-running loops. Fine-grained per-function performance metrics (similar to what Simpleperf provides for Android), allows comparing metrics before and after sanitizers and provides the easiest means to identify hot functions. These functions can either be refactored or, after manual inspection to verify that they are safe, have sanitization disabled.

Sanitizers can be disabled either inline in the source or through the use of ignorelists and the -fsanitize-ignorelist flag.

The physical layer code, with its extremely tight performance margins and lower chance of exploitable vulnerabilities, may be a good candidate to disable sanitization wholesale if initial performance seems prohibitive.

Soaking in Pre-production

With overhead minimized and shallow bugs resolved, the final stage is enabling the sanitizers in trapping mode to mitigate vulnerabilities.

We strongly recommend a long period of internal soak in pre-production with test populations to uncover any remaining violations not discovered in testing. The more thorough the test coverage and length of the soak period, the less risk there will be from undiscovered violations.

As above, the configuration for trapping mode is as follows:

-fsanitize=signed-integer-overflow,unsigned-integer-overflow,bounds -fsanitize-trap=all

Having infrastructure in place to collect bug reports which result from any undiscovered violations can help minimize the risk they present.

Transitioning to Memory Safe Languages

The benefits from deploying sanitizers in your existing code base are tangible, however ultimately they address only the lowest hanging fruit and will not result in a code base free of vulnerabilities. Other classes of memory safety vulnerabilities remain unaddressed by these sanitizers. A longer term solution is to begin transitioning today to memory-safe languages such as Rust.

Rust is ready for bare-metal environments such as the baseband, and we are already using it in other bare-metal components in Android. There is no need to rewrite everything in Rust, as Rust provides a strong C FFI support and easily interfaces with existing C codebases. Just writing new code in Rust can rapidly reduce the number of memory safety vulnerabilities. Rewrites should be limited/prioritized only for the most critical components, such as complex parsers handling untrusted data.

The Android team has developed a Rust training meant to help experienced developers quickly ramp up Rust fundamentals. An entire day for bare-metal Rust is included, and the course has been translated to a number of different languages.

While the Rust compiler may not explicitly support your bare-metal target, because it is a front-end for LLVM, any target supported by LLVM can be supported in Rust through custom target definitions.

Raising the Bar

As the high-level operating system becomes a more difficult target for attackers to successfully exploit, we expect that lower level components such as the baseband will attract more attention. By using modern toolchains and deploying exploit mitigation technologies, the bar for attacking the baseband can be raised as well. If you have any questions, let us know – we’re here to help!